by Prosanta

Chakrabarty and Matt Davis

May 2010

In late January to early February of this

year, my postdoc Matt Davis and

I traveled to Vietnam to collect some marine fishes from markets. Every year I

try to make a trip to Asia to collect rare fishes for the LSU fish collection

and for phylogenetic study. The large open markets of Asia allow us to collect

a diverse number of species in a relatively short amount of time. Instead of

hiring a trawler (upwards of $10K a day) it’s easier to hang out on the docks

to grab some freebies off the boats. Typically we collect early in the morning

and spend the rest of the day processing the fish (voucher, label, tissue

sample, preserve, etc.). Because of the great quantity of fish that we were

dealing with it really did take nearly the entire day to process the specimens

from each morning’s haul. On this trip we collected roughly 400 different

marine species and more than 2,000 specimens in two weeks. We also had a couple

of days to do some fresh/ brackish water collecting on the Mekong Delta. The

Mekong is one of the world’s oldest and oddest rivers and is home to car-sized

catfish, giant stingrays, and other behemoths of the fish world.

Vietnam

is a long narrow country that spans several biotic regions including the Mekong

Delta, South China Sea, and Gulf of Thailand. We saw long stretches of amazing

beaches, and miles of huge inland sand dunes directly abutting verdant green

rainforest. It is also culturally diverse. We saw signs of socialist pride (the

old Soviet hammer and sickle was ubiquitous) and French imperialism (baguettes

and wrought iron abound), mixed with an Indo-Thai- Chinese culture found

nowhere else. The people were extremely courteous and amiable, sometimes too

much so, making for a fun cultural experience. Matt in particular was gawked at

constantly for being a giant white man with funny colored straight hair.

Matt and I traveled with four Taiwanese

colleagues that had previous experience collecting in Vietnam. It was my first

time traveling in Asia without locals to help translate (as the Taiwanese spoke

no Vietnamese). This made for some funny and frustrating situations.

During

our trip we traveled to Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), and the beautiful beach

towns of Mui Ne and Nha Trang. The first two things that stood out about Ho Chi

Minh City included the amazing diversity of food and the incredible numbers of

scooters – the many, many scooters. These scooters zoomed past and parted

around you like a school of fish. For the most part there were no traffic

signals or even traffic patterns, just a free for all of scooters, taxis, and

buses. Many large cities in Asia have similar numbers of scooters on the

streets, but they all had some semblance of organization. Our Taiwanese colleagues,

who ride scooters in Taiwan quite often, would not rent scooters in Ho Chi

Minh, and often remarked how “they drive crazy here.” To cross a street in

Vietnam you have to walk deliberately into the non-stop flow of traffic keeping

a steady pace so that the traffic will move around you. Amazingly it works,

although I thought each time that I would be maimed. When we left Ho Chi Minh

we ended up on scooters ourselves to travel between fishing ports. Even in

these less populated areas weaving in-and-out of traffic and speeding on the

“wrong side” was still a common occurrence.

After a while you get used to it, and even I

went out on my own a few times with my little rented ”motobike” to relax and

blow the smell of fish out of my clothes.

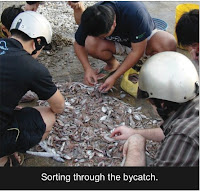

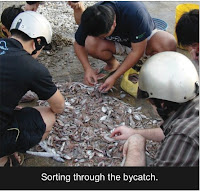

The

markets we visited (more than 20 in all) were mostly small artisanal fisheries

from local fisherman collecting on the South China Sea. The fishes that we were

collecting were not always being sold at the market but were often part of the

rubbage pile of bycatch. As in most cases the bycatch piles are chock full of

strange fishes that no one would purchase for their dinner. It was in these

piles that we collected odd silvery eels, fatheaded jawfishes, fleshy dark

deepsea fishes, and numerous other oddities that we ichthyologists crave. The

markets themselves were also remarkably diverse matching the diets of the

locals. You know if the Vietnamese weren’t eating them that the fish must look

very strange.

Matt, who the Taiwanese referred to as “Max” the

entire trip, was after some of the fish he studied during his dissertation, in

particular the lizardfishes. Lizardfishes include cigar-shaped predatory fishes

that dwell along the bottom of the continental slope to depths of around 200

meters. Of particular note were specimens collected of the only mesopelagic

lizardfish genus Harpadon, commonly known as the “Bombay Duck” and found

only in the Indo-Pacific. (The nickname comes from Indian restaurateurs trying

to make the fish sound more appetizing to British diners.) Dried Harpadon is

considered a delicacy in parts of Asia, and indeed we often spotted hundreds of

dried out specimens lying on the street, a sight that would make Matt cringe each time. In the end we

managed to procure quite a few fresh specimens, including a potentially new

species that exhibits sexual dimorphism.

Near the end of the trip we

went out collecting on the Mekong Delta. It took some work getting to the

Mekong and hiring a boat but once aboard we would ask our driver (ask as in point

to a boat and to a picture of a fish) to take us toward the small fishing boats

trawling the Mekong. It was by trading with boatman that we collected some of

the most interesting freshwater and brackish water specimens. Nearly every

specimen collected is new to the LSU collection, and some are certainly new to

science. The products of the trip will be additional materials for our on going

projects on the family level phylogenies of some notable deepsea,

bioluminescent, and otherwise poorly studied Western Indo

At the end of June, my PhD student

Bill Ludt and I went to Okinawa for the 9th Indo-Pacific Fish Conference

(IPFC), and then traveled to Tokyo to do a market survey and collection at the famous

Tsukiji Market. The IPFC is held every 4 years and it is a mix of an

ichthyology and evolution conferences that is important for everyone working on

fishes in the region. This year’s conference was particularly important for me because

it included a Percomorph Symposium that dealt with higher-level fish

systematics and included a series of well-known and well-respected speakers

(obviously I wasn’t invited to speak), and it was one of the most important

single days in systematic ichthyology signaling in a paradigm shift in our

discipline.

At the end of June, my PhD student

Bill Ludt and I went to Okinawa for the 9th Indo-Pacific Fish Conference

(IPFC), and then traveled to Tokyo to do a market survey and collection at the famous

Tsukiji Market. The IPFC is held every 4 years and it is a mix of an

ichthyology and evolution conferences that is important for everyone working on

fishes in the region. This year’s conference was particularly important for me because

it included a Percomorph Symposium that dealt with higher-level fish

systematics and included a series of well-known and well-respected speakers

(obviously I wasn’t invited to speak), and it was one of the most important

single days in systematic ichthyology signaling in a paradigm shift in our

discipline.